When the Supreme Court on Oct. 3 hears the Wisconsin redistricting case, the legal conflict will pit a relatively narrow argument that is based on Court precedents against a broader-based approach based on constitutional history and good-government arguments. The clash also will likely explore the practicality of the reformers’ proposed mathematical remedy that has been designed by a political science scholar, which was approved by the three-judge federal court that earlier this year overturned the Wisconsin redistricting plans.

That prospect emerges from a reading of the roughly 50 “amicus” briefs that have been filed on behalf of the two sides. Although Supreme Court debates—and rulings—can move in unexpected directions, the written arguments typically foreshadow the courtroom exchange and the principles that the Justices ultimately will cite.

The lawyers’ filings also reinforce the expectation that the outcome of the Wisconsin case will swing on the decision of Justice Anthony Kennedy. Both sides repeatedly cite for their own purposes his swing vote in a 2004 case that potentially opened the door to sweeping restrictions on redistricting plans. In that Pennsylvania case, Kennedy ultimately was unwilling to accept the reformers’ arguments but he invited further study and proposals on the topic.

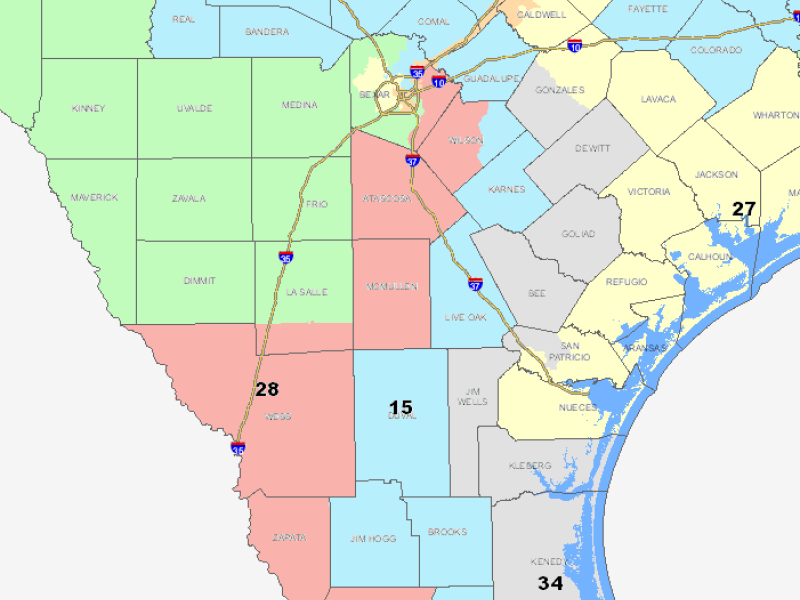

Although five of the current Justices have taken office since the 2004 ruling, they appear to have taken sides in a similar liberal-conservative breakdown. That dynamic was reinforced in early September when the Supreme Court delayed implementation of lower-court decisions that would impose changes on Texas redistricting maps for its congressional delegation and the Legislature. In that case, Kennedy again joined conservatives in a 5-4 vote that blew the whistle on reformers, at least temporarily.

Apart from the substance of their appeals, the briefs for the Wisconsin case offer notable organizational contrasts among the groups that submitted the filings. The briefs on behalf of the Wisconsin maps have been written chiefly on behalf of that state’s Republican-led Legislative and Executive branches and their local interest-group allies, plus national GOP organizations. The briefs that oppose the Wisconsin line-drawing—and seek to sustain the lower-court ruling—have been written primarily by national liberal advocacy groups, diverse bipartisan mixes of current and former Members of Congress, and an array of professors from such disparate fields as geography, history and mathematics.

No Democratic Party group made filings to challenge the controversial maps, nor did any Republican Member of Congress join the other side to defend the maps. Those tactics highlight the growing complexities of the political debate as the states prepare for the next decennial redistricting, prior to the 2022 elections. At the very least, the Supreme Court’s ruling in the Wisconsin case likely will shape the legal battleground following the 2020 Census and nationwide reapportionment.

The Court case has been accompanied by a growing public debate of the merits of what critics on the Left increasingly refer to as “extreme partisan gerrymandering.” Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg has cited the Wisconsin conflict as the most important case facing the Court in its new term, which starts Monday. Former President Barack Obama and Attorney General Eric Holder have launched a high-profile campaign to urge a more coordinated approach by Democrats.

Ironically, the disputed Wisconsin map has bolstered the Republican margin in that state’s 1st District, which is represented by Speaker Paul Ryan. If the Court rules against that map, the outcome could be a significant blow to Ryan’s House GOP Conference.

Among the intriguing briefs in the current showdown have been separate arguments on behalf of more than a dozen Republican state attorneys general defending Wisconsin and a similar number of Democratic attorneys general objecting to the controversial maps.

“The Court has never held that a State violates the Constitution by pursuing or achieving political goals through reapportionment,” argued the GOP group, led by Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton. “The district court’s decision invites openly partisan policy battles in the courtroom. This will expose every State to litigation under a legal standard so indeterminate that any party that loses in the legislature has a plausible chance of overriding that policy decision in the courts. The Constitution does not support, let alone compel, this result.”

The Democratic group, led by Oregon Attorney General Ellen Rosenblum, made a very different argument. “Intentional partisan entrenchment—that is, deliberately drawing districts for the purpose of keeping one party in power for the long term, and without any neutral justification for the result—has no place in our political system…. Technological advances have made it easier than ever for mapmakers to draw district lines solely to maximize the political power of a particular party. There is a pressing need for the courts to identify a manageable legal standard that prohibits the most egregious examples of partisan gerrymandering while still respecting the legitimate considerations that inform redistricting decisions.”

The legal briefs created a wide-ranging discussion of the so-called “Efficiency Gap,” a complex calculation to determine whether state redistricting maps comply with what proponents contend are the political norms of each state. That mathematical formula was crafted by Eric McGhee, a political scientist and research fellow with the non-partisan Political Policy Center of California, which is based in Sacramento. It was formally approved by the court in its Wisconsin ruling, though the two judges in the majority did not explore in detail its premises or implications.

In his brief to the Court, explaining how the formula works, McGhee wrote, “(T)he EG is a practical, historically grounded implementation of partisan symmetry—the relative opportunity for each party to convert votes into state legislative or congressional seats. An EG of zero mathematically indicates symmetry, and, further, that the relationship between the parties’ vote shares and seat shares under the map at issue aligns with the historical norm in state legislative and congressional elections.” As described by McGhee, “A party’s wasted-vote total is subtracted from the other party’s wasted-vote total, and the difference is divided by the total number of votes in the election. The result—the EG—is the difference in wasted votes as a percentage of the total vote.”

Critics of the lower-court rulings harshly attacked the concept in their amicus briefs. Various Supreme Court rulings have been “premised on the fundamental belief that voters are not fungible deterministic party automatons,” the Republican National Committee wrote. “Rather, political debate, each party’s platform, and the candidates nominated to run in each election are the primary determinants of how an election will turn out. The efficiency gap’s assumptions about, and treatment of, voters is flatly contrary to these lines of authority.”

According to the National Republican Congressional Committee, “The ‘Efficiency Gap’ is in reality nothing more than an attempt to impose a state-wide proportional vote requirement for legislative bodies on the basis of statewide vote for candidates,” which courts have repeatedly ruled is unconstitutional. Lawyers for the Wisconsin Senate and House made a similar argument. Lawyers supporting the lower-court ruling did not necessarily embrace the “efficiency gap” formula. “That the courts have not yet converged on a single definitive formula to make out a partisan-gerrymandering violation is no reason to quit the project,” Common Cause wrote.

The League of Women Voters cautioned not to “elevate form over substance,” noting that Wisconsin’s “apparent compliance with traditional redistricting principles of compactness, contiguity, and respect for political subdivisions” should not be “automatically constitutional,” and “would ignore the reality that increasingly sophisticated technologies allow legislatures to cloak intentional, extreme partisan gerrymanders in ‘normal’-looking districts.

At least four separate briefs were filed on behalf of several dozen current and former Members of Congress from both parties who cited the dysfunction and polarization in Congress as they urged the Court to overturn the Wisconsin maps. “Extreme partisan gerrymandering harms our political system, and harms the functioning of the House in particular,” wrote a group of 34 current and past House Members, including eight Republican incumbents. “A cascade of negative results predictably follows: artificially drawn ‘safe’ districts make the general election uncompetitive and give party insiders and a small core of ‘base’ primary voters wield greater influence than the general electorate; political parties gain influence and obstruct independent, constituent-first representation; compromise with the other side becomes politically impossible….”

“When a plan is drawn—as Wisconsin did here—to entrench a political party in power over the life of the plan and even in the face of an electoral swing to their political opponents, it violates the fundamental constitutional principle that ‘the voters should choose their representatives, not the other way around’,” wrote a group that included current House Democrats, including Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi, and another bipartisan mix of former members.

Taking issue with their party organizations, Gov. John Kasich, R-Ohio, and a dozen former GOP statewide elected officials, including former Sen. Bob Dole of Kansas, wrote, “If this Court does not stop partisan gerrymanders, partisan politicians will be emboldened to enact ever more egregious gerrymanders as ever more precise voting data continually become available. That result would be devastating for our democracy.”

The Wisconsin case offers abundant evidence that redistricting will continue to encourage full employment among lawyers, political consultants and their technical wizards. The Supreme Court’s ruling will help to determine whether mathematicians and other academicians will gain more influence on the battle field.

Richard E. Cohen is Chief Author of The Almanac of American Politics. For more insights, including profiles of all Members of Congress and the governors, order your copy of the Almanac from www.thealmanacofamericanpolitics.com.

Image: AP Photo/Scott Bauer

Subscribe Today

Our subscribers have first access to individual race pages for each House, Senate and Governors race, which will include race ratings (each race is rated on a seven-point scale) and a narrative analysis pertaining to that race.