With Saturday’s gubernatorial runoff in Louisiana, the 2019 odd-year elections are now in the record books. Did Democrats capturing the governorship of Kentucky and reelecting a governor in Louisiana, though coming up short in Mississippi, mean anything? Are these results canaries in the proverbial coal mine or just random events?

There are a couple of things that can always be counted on after big elections. The winning side will invariably say that it is the most consequential election since Athenians fully developed democracy around 500 BC, and that the outcomes portend great things for that party in both the short and long term. Similarly, the losing side can be expected to say that, notwithstanding everything complimentary that had been said before the election, both their candidate and campaigns were terrible, and that exogenous factors prevent any meaning to be drawn from the outcome.

Both Democratic gubernatorial wins occurred in reliably Republican states, contests that the GOP shouldn’t have to worry about. A strong case can be made that incumbent Gov. Matt Bevin lost in Kentucky despite the fact that he was a loyal Trump Republican, not because of it. In Louisiana, incumbent John Bel Edwards won despite the fact that he is a Democrat, not because of it.

It no secret that Bevin was highly skilled at making enemies, both in his own party and those outside. As Democratic Rep. John Yarmuth so artfully put it in The Washington Post, “Matt Bevin is kind of the antithesis of any politician I’ve ever been around in that he seems to get up every day and decides, ‘Well, who am I going to piss off today?’” Given the direction in Kentucky politics in recent years, that is probably what it would take to lose. The governorship has alternated between the parties since 1995, but that masks a trend towards the GOP. The last non-Southern Democrat to carry the Bluegrass State in a presidential election was Adlai Stevenson (from Illinois) in 1952. Democrats only hold one of the state’s nine Senate and House seats. Of the six statewide elected officials on the ballot this year, Bevin was the only Republican to lose, if only by less than 5,000 votes.

At the same time in Louisiana, Edwards was about the closest thing to a political unicorn as there is in today’s politics—a pro-gun, pro-life, West Point graduate, Army Ranger getting elected as a Democrat. Prior to Edwards’s election four years ago, Republicans had won four out of the previous five governor’s races in the state, and going into this election, Edwards was the only Democrat of the seven statewide elected state offices and was the only Democrat to win statewide this year as well. The only times that Democrats have carried Louisiana since John F. Kennedy won the state in 1960 have been the three Southerners—Lyndon Johnson in 1964, Jimmy Carter in 1976, and Bill Clinton in both 1992 and 1996 (Alabaman George Wallace, running as an independent, carried the state in 1968). Had scandal-plagued Sen. David Vitter not been the Republican gubernatorial candidate four years ago, it is extremely doubtful that Edwards would have won then. But Republicans also had to contend with the lingering hangover from Bobby Jindal’s eight years as governor. Whether in poll numbers or state-budget deficits, Jindal left quite a mess that didn’t help them hold onto the governorship.

Even in Mississippi, the open governorship that the GOP held, Republican Lt. Gov. Tate Reeves's 52-to-47 percent victory over Democratic state Attorney General Jim Hood was not impressive in a state that Trump carried by almost 18 points and where Republicans routinely run up much bigger wins.

So, are we to disregard these outcomes? To say that Beshear and Edwards didn’t earn their wins is totally wrong; they had to be awfully good to have any chance of winning given where they were running. But we frequently see very capable and well-funded candidates in both parties run excellent campaigns in very tough states or districts and come up short. There are some undertows that even a Michael Phelps can’t swim through. It’s the same in politics. Sometimes being either lucky or good still isn’t enough; you have to be both lucky and good.

In 2018, Republicans did well in small-town and rural America, but they were quite fortunate that the Senate battlegrounds were in mostly red states where President Trump was quite popular, helping the GOP score a net gain of two seats. Urban America was awful for Republicans, but that is nothing new. The change was in the suburbs, where college-educated voters, more women than men, turned against the GOP in a very big way, costing them the House but also helping Democrats score gains in governorships and state legislative seats.

But what can we take out of 2019? While it is true that state elections are not fought on the same issue terrain as federal races, we are seeing an increased nationalization of American politics. The hyper-partisanship and tribalism that started in federal contests has now reached into state and, in some cases, even local races.

There is very little in the way of election results this year or polling data, national or state-level, that should give Republicans much encouragement. While it’s more than a little dishonest to blame Trump for the GOP losses in Kentucky or Louisiana, the fact is he went in and put a lot on the line. He visited Louisiana three times and Kentucky once in the closing weeks of the campaigns, practically begging those attending his rallies to vote Republican for his sake if no other. It didn’t work.

Those suburbs were disaster areas for the GOP in 2018, and they didn’t look any better in 2019. Just a quick look at the northern Kentucky suburbs, near Cincinnati, shows they did not perform for the GOP the way they should have. In Louisiana, Jefferson Parish, just outside New Orleans, is one big suburb, essentially the birthplace of the Republican Party of Louisiana. Edwards won 57 percent of the vote there.

The reality is that the most convincing wins for Democrats were in lower-level offices that didn’t have the extenuating circumstances of Kentucky and Louisiana. In Virginia, a once-red state that trended purple for the last decade and is now starting to turn blue, Democrats captured both the House of Delegates and the Senate, along with the governorship. That’s the Virginia trifecta, and that’s with redistricting coming in two years.

Democrats gained control in the November elections of the suburban Philadelphia county councils in Bucks, Chester, and Delaware Counties. In the case of Delaware County, Republicans have held it since the Civil War; Democrats picked up two seats on the five-member council in 2017, then won the other three this year, a sweep in the county that long-featured the last urban Republican political machine in the country.

You can explain away some of these results, but not all of them.

This story was originally published on nationaljournal.com on November 19, 2019

Subscribe Today

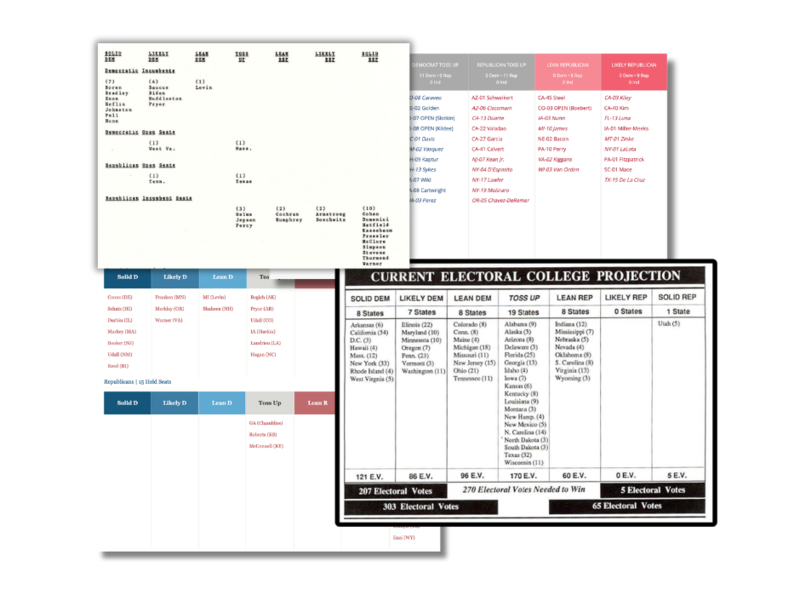

Our subscribers have first access to individual race pages for each House, Senate and Governors race, which will include race ratings (each race is rated on a seven-point scale) and a narrative analysis pertaining to that race.